We can use the snap list command, as shown below, to list the installed snap packages: snap list

#Snap package manager centos install

This is an Ubuntu distribution, so some snap packages are installed right out of the box, and we’ve just installed another one.Īdditionally, when you install snapd, it installs some core snap packages to handle the needs of other snap packages. However, this doesn’t mean there are 18 different snap packages installed on this computer. A /dev/loop device file handles each one, and there are 18 of them.Įach file system is mounted on a directory within the /snap directory. The mounted SquashFS file systems are listed. We’ll use the – t (type) option to limit the output to SquashFS file types only. We can use the df command to quickly check this. The “18” means this is the 18th /dev/loop device file in use on this Linux computer. In this case, they’re mounting the SquashFS filesystem within the snap package. They’re typically used for mounting the file systems in disk images. Loop device files are used to make regular files accessible as block devices. The file system is listed as: /dev/loop18.

#Snap package manager centos how to

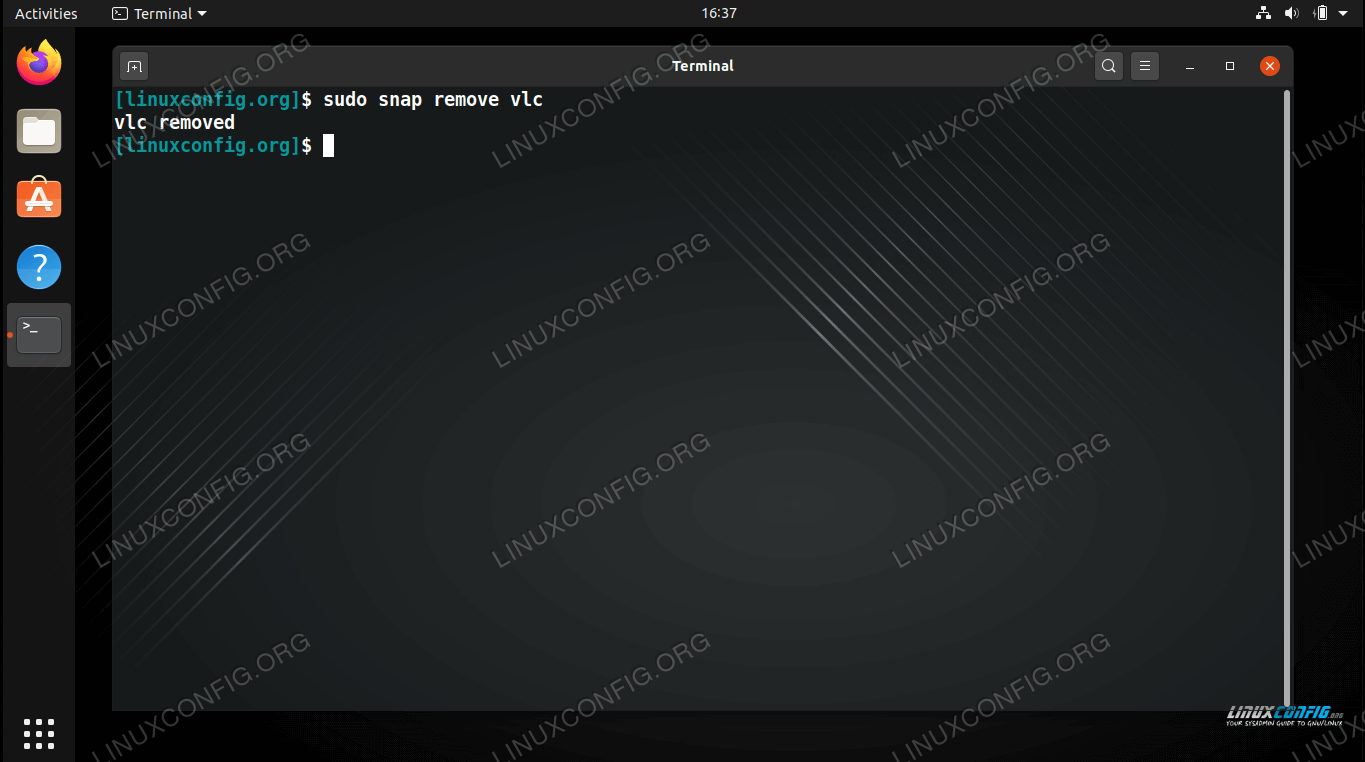

RELATED: How to Use the grep Command on Linux The “252” is the release number of this version of gimp. The mount point is in the snap directory here: /snap/gimp/252. This shows us the snap package was mounted as though it were a file system. If we pipe its output into the grep command and search for “gimp,” we isolate the entry for the package we just installed. You can use the df command to check the capacity and usage of the different file systems configured on your Linux computer. To install snapd on Fedora type the following command: sudo dnf install snapdĪs it downloads, the percentage completed figure rises and a progress bar creeps across from the left of the terminal window. When the installation is complete, a message appears (as shown below) telling you the package was installed. Behind the scenes, the snapd daemon is also the name of the package you have to install if you don’t already have Snappy on your computer. Snap is both the name of the package files and the command you use to interact with them. On our machine, Snappy was installed on Manjaro 18.04, but we had to install it on Fedora 31. Snappy was introduced with Ubuntu 16.04, so if you’re running that version or later, you’re already good to go. This is the trade-off for the simplicity of the install, and the removal of the resource-conflict headaches, though. If two different snap applications require the same resources, they each bring their own copy. It’s also easy to duplicate a resource you’d normally only install once, such as MySQL or Apache. Of course, because each package file must contain every resource the application needs, the package files can be large. All you’ll know is you’ve installed an application, and, now, you have access to it. All of this takes place behind the scenes. It’s then presented to you as a virtual environment. If they’re not installed in the usual way, though, how are they handled? Well, the single package file is downloaded, decompressed, and mounted as a SquashFS virtual file system. You can even install and run applications that need conflicting library versions because each application is in its own sandbox. They aren’t installed in the traditional sense, so they don’t cause any problems with other applications that require different versions of the same resources. The libraries and other resources the application is packaged with or requires are only available to it alone. These systems encapsulate the application together with any dependencies and other requirements in a single compressed file. The application then runs in a sort of mini-container. It’s sandboxed and separated from other applications. AppImage and FlatPack are others you might have encountered. It’s based on a packaging and deployment system called Click, which harkens back to the Ubuntu Touch initiative. Snappy is one of the more popular of these. One solution to these problems is application packing and deployment systems. Or, if you use two applications that clash because they’re tied to specific-but different-versions of a library. However, you still face a struggle if you need different versions of the same application installed. This has improved with better package management systems, like apt, dnf, and pacman. You’d then hunt down the missing resource and install it, only to find another application depended on the version of the library you just replaced. You’d install something only to find a particular library or other dependency was missing or outdated. In the past, installing applications on Linux was a potentially frustrating experience.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)